Title: Breaking Barriers (An Autobiography)

Publisher: Diamond Communications Network, Abeokuta

Author: Modupe Adekunle

Reviewer: Reuben Abati

Year: 2015 | Pages: 193

[dropcap]B[/dropcap]reaking Barriers is the title of the autobiography of Mrs. Modupe Abibat Adekunle who retired from the Ogun State civil service on September 30, 2015, upon her completion of the statutory 35 years in service. This book has been published to put on record, the highlights of her experience as a career public servant, and also to tell the story of her life as she attains the age of 60 on November 11, 2015. It is essentially a civil servant’s narrative: completely shorn of politics, polite, appreciative, stays within the limits of obligations, not giving any state secrets away, not violating any rules and regulations, and full of lessons. It is a book that all categories of readers will find useful and instructive, be they parents, young persons seeking a life of meaning, civil servants, public administrators, labour unionists, or the general reader.

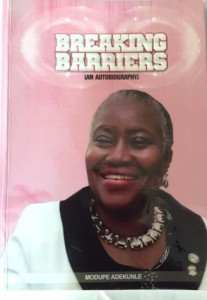

Mrs. Adekunle takes us through a linear, chronological account of her life in nine chapters, but at first blush, the title of her story attracts special interest, and perhaps deserves a little interrogation. Breaking Barriers, says the cover page of the book, with Mrs Adekunle’s photo, a broad smile on her lips, on a background of pink colour. For those familiar with the art of suggestion, the cover of the book is a teaser, an invitation to curiosity. In a society where despite the many advancements that have been made by Nigerian women in all walks of life, gender inequity remains a problem and the objectification of women an abiding social nuisance, when a woman says she has broken barriers, and smiles triumphantly, the tendency is to assume that she has broken through the proverbial glass ceiling and that her story is one of triumph against gender discrimination. But this is not one of such womanist or feminist books. The barriers of Mrs Adekunle’s personal world are of a different kind.

Nowhere in her narrative does she give any impression or tell any story about having been discriminated against on account of being a woman. On the contrary, her world is peopled by appreciative parents and brothers, a supportive husband whose story she tells with the relish of a young lady meeting her Prince Charming, colleagues with whom she enjoyed excellent work relations, doting inlaws, and life-long friends. The day she was born, November 11, 1955, her father, S.M. Duze, was so excited he ran out of the hospital with joy. He already had five boys. He wanted a daughter. When she arrived, he couldn’t contain his joy. That affection we are told, “remained throughout his life time.” Mrs Adekunle grew up in a household of nine children, where there was “lots of fun”, story-telling, and love. During her secondary school days, at Queen’s College, Ibadan, she was the President of the Literary and Debating Society, and was actively engaged in sports: hockey and volleyball; she soon became so proficient in the former, that she played hockey at the First, Second and Third National Sports Festival while an undergraduate student at the University of Ibadan, and was in that regard, the Vice Captain of the Western State Hockey Team. Even after her National Youth Service, at the Bauchi State Sports Council, and she had married and become a mother, she was again invited by the Oyo State Sports Council to represent Oyo state at the Fourth National Sports Festival in 1979. “My time on the hockey pitch still holds very sweet memories for me. I thoroughly enjoyed myself and I never had any worries while on the pitch. It could so engross me that I would forget to study my books; that was how committed I was to the game,” she writes.

Nowhere in her narrative does she give any impression or tell any story about having been discriminated against on account of being a woman. On the contrary, her world is peopled by appreciative parents and brothers, a supportive husband whose story she tells with the relish of a young lady meeting her Prince Charming, colleagues with whom she enjoyed excellent work relations, doting inlaws, and life-long friends. The day she was born, November 11, 1955, her father, S.M. Duze, was so excited he ran out of the hospital with joy. He already had five boys. He wanted a daughter. When she arrived, he couldn’t contain his joy. That affection we are told, “remained throughout his life time.” Mrs Adekunle grew up in a household of nine children, where there was “lots of fun”, story-telling, and love. During her secondary school days, at Queen’s College, Ibadan, she was the President of the Literary and Debating Society, and was actively engaged in sports: hockey and volleyball; she soon became so proficient in the former, that she played hockey at the First, Second and Third National Sports Festival while an undergraduate student at the University of Ibadan, and was in that regard, the Vice Captain of the Western State Hockey Team. Even after her National Youth Service, at the Bauchi State Sports Council, and she had married and become a mother, she was again invited by the Oyo State Sports Council to represent Oyo state at the Fourth National Sports Festival in 1979. “My time on the hockey pitch still holds very sweet memories for me. I thoroughly enjoyed myself and I never had any worries while on the pitch. It could so engross me that I would forget to study my books; that was how committed I was to the game,” she writes.

She displayed this same devotion and commitment in her career as a civil servant, after a brief stint as a teacher, having joined the Ogun State Civil Service on the 30th of September 1980. That 35-year journey which ended on September 30, 2015, began with her appointment as an Administrative Officer in the Ogun State Civil Service, and her first posting to the Administration and Finance Department in the then Ministry of Home Affairs. In four chapters, the author draws attention to the major landmarks of her career. Serving civil servants, or those starting out in their careers will find this section of the book, particularly instructive: what qualities took Mrs Adekunle to the top of her career? How did she manage to juggle her multiple responsibilities as a wife, mother, unionist and career civil servant, and still succeed on all fronts? The answers are not far to seek: commitment to every task at hand, the love of excellence, honesty, hardwork, discipline, selflessness, and as she herself further puts it: “I believe it is the Grace of God…And that same grace gave me many opportunities to serve others using the leadership mantle that was thrust upon me.” (p.77).

From her own account, in every Ministry or Department where she worked, her bosses were always reluctant to allow her to be posted to another Ministry. Responsibilities were assigned to her, and she served diligently. It is precisely this reputation for diligence and honesty that saw her ending up as a labour leader within the civil service. In 1987, she was invited to join the Association of Senior Civil Servants of Nigeria. Although she did not take part in the elections, she was elected Treasurer, because the then prospective Chairman of the Ogun state Chapter, Mr Adekunle Anwo had insisted he could only lead the association with Mrs Adekunle as Treasurer. Given the widespread perception of civil servants, with regard to money matters, and the rot within the civil bureaucracy, there could have been no better commendation than this. It nonetheless marked the beginning of a new and momentous phase in Mrs Adekunle’s career. She eventually served the association as Acting Chairman, and Chairman; also as Chairman of the Negotiating Council (Trade Union) and as National Vice President.

As a labour leader, she presided over the longest workers’ strike in Ogun State: her account of the 31-day strike that brought the Ogun State government to its knees is worth reading for the insights she offers into unionism, negotiations, collective bargaining, the challenges of leadership, the importance of communication, and the attitude of the followership in an industrial strike situation. Her revelation that the support of workers is crucial even when as a labour leader you are defending their cause is noteworthy, for there could be situations whereby the workers themselves could sabotage the strike. So, she writes: “This happened so many times till we realized during one of the strikes that nearly everyone was back at work and the union leaders were the only ones not at work…the followers weren’t following” (p.91).

Her days of frontline unionism came to an end with her appointment as a Permanent Secretary in January 2010. On December 21, 2011, she was appointed Head of Service. In these senior positions and as the foremost civil servant in the state, Mrs Adekunle’s report of her tenure further indicates a commitment to workers’ welfare, and ensuring that bureaucracy is brought in line with the development objectives of the administration to ensure effectiveness, efficiency and a people-oriented management system at all levels.

She remained on duty till her last working day, and in looking back, she says: “I retired as a much fulfilled woman” (p. 124). The testimonials reproduced in the book show clearly that she was highly regarded for her contributions. Senator Ibikunle Amosun, the Governor of Ogun State says she is a “quintessential civil servant” and adds: “Looking back, I testify that Mrs Adekunle discharged the duties of her office with dedication and uncommon loyalty. She worked so hard and well that she naturally emerged as the Head of Service. She has etched her name in the annals of the history of our dear state. In decision making, once she is convinced on the right and proper course, in the larger interest of her constituency, the Civil Service, she stood by her convictions and was never afraid to take a position, even if such position appears to be unpopular in the short term.” Elder Adekunle Anwo further testifies that “those who were privileged to work with Mrs Modupe Adekunle will readily recall that she was a team player, a strategic thinker, a socialite, a visionary and courageous leader of immense intellect, very innovative, painstaking, proactive and creative.” (p. 190)

So, where are the barriers, then? As stated earlier, there is no indication in this book, of Mrs Adekunle ever being discriminated against in the course of her career, on the grounds of her being a woman, if there was any such incident at all, she didn’t consider it material enough to write about it, but she was a victim of political victimization on account of her involvement in union activities. For about ten years, she was passed over during promotion exercises and her juniors were promoted over and above her. She reports that “during most of our standoffs and negotiations which were usually with the State Government, I was in the forefront and very visible” (p.82). Her reward for this in another instance was her being posted to an office that had no toilet facility and she had to go to other offices to use their toilets. A toilet could not be provided for her office because “this was not covered under the budget” (p. 94). In the end, she triumphed.

The other major challenge, which could have become a career-threatening barrier was her “battle against breast cancer” (pp. 98 -105). In June 2009, she discovered a lump, that resulted in rounds of chemotherapy at the University College, Hospital, Ibadan (UCH) up till January 2010. It was a difficult period for her, having to combine work with looking after her health, and having to climb about 60 or 72 steps to get to her office at the Bureau of Cabinet and Special Services, panting, gasping, and having to be assisted up the stairs by her secretary. Even in that condition, she refused to stay away from work. But she broke the cancer barrier, became Permanent Secretary and subsequently Head of Service and completed her 35 years in service.

Another barrier that is worth underlining, was the protracted battle she had to fight against political leaders, with no public service experience who insisted on violating “Public Service Rules”, and would rather treat civil servants shabbily including the example of a certain Governor who, had he been allowed, could have brought “someone from the motor park to become a Permanent Secretary” (p. 96). Mrs Adekunle insisted on the rules and stood her ground under such circumstances. What she fails to add perhaps is that sycophantic, anything-Oga-wants, civil servants are the very ones who often misguide such political bosses.

The other barriers are not major episodes in this narrative but they are nonetheless significant in the context of traditional realities in our society. Born a Muslim, she is married to a Christian and has since become a Christian by marriage. In some other relationships, this could be a big barrier. She is also the biological mother of two daughters, in some other families given the obsession with male children in Africa, this could also have been a problem. But not for Mrs Adekunle and her husband, whose personality she says complements hers. She is originally from Edo State: her father is from Ukpeko, near Ewu town in Ishan, and her mother, from Agbede, Edo State, but she is married to the Adekunles of Abeokuta, Ogun State, and yet she rose rightfully and by popular acclamation, to the position of the Head of the Civil Service of Ogun State. There have been stories elsewhere in Nigeria of women in inter-ethnic marriages, being discriminated against on the grounds of indigeneship even when they have worked in their husband’s state of origin for decades. Not so in Mrs Adekunle’s case: she has had a life-long successful career among her husband’s very enlightened people.

This is a book about service and leadership. It is also invariably about people, family and parenthood. Mrs Adekunle writes about her childhood, growing up years, her own family and children, her husband’s family and about friends and colleagues. She comes across as an all-round fulfilled woman at 60. Whatever travails she may have encountered, she does not write with any trace of bitterness, and although she says she, unlike her husband, likes to extract a pound of flesh from adversaries, she does not do so in this book. It is a calm narrative, full of humour, a sprinkling of childhood-era folktales as told by her parents and brothers (these days, parents no longer tell their children stories, DSTV, computer games and nannies have replaced parents), all richly illustrated with photographs of significant moments in her life, from Enugu where she was born to Abeokuta where she is now at 60, wife, grandmother, and retired Comrade Head of Service.

Perhaps the book could have been further enriched if Mrs Adekunle had attempted an assessment of the civil service as it is today and offered suggestions as to how it can be further reformed and strengthened. For, let’s face it, the civil service in Nigeria is still in dire need of reform and innovation. But she has restricted herself to telling her own story so that others may learn from it. “I have personally told my story”, she tells us, “not for the fun of it but in anticipation that you will be able to grab something from it. After evaluating my life, the barriers and the successes, I have come to the conclusion that there is no challenge in life that is insurmountable, including health and financial challenges….” (p.137). This is quite true. Different categories of readers have a lot to learn from Mrs. Adekunle’s story. Breaking Barriers deserves the attention of the reading public.

Dr. Reuben Abati was Spokesman and Special Adviser, Media and Publicity to President Goodluck Jonathan (2011 – 2015). He tweets from @abati1990. This review is culled from his website, Reuben Abati.

The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the writer.