In the opening paragraph of his short biography of Professor Bénézet Bujo, published in 2003, and titled, “Bènèzet Bujo: The Awakening of a Systematic and Authentically African Thought”, Juvenal Ilunga Muya, writes:

“Bénézet Bujo was born at Drodro, Democratic Republic of Congo, in 1940. We can distinguish three stages in his intellectual journey: the first, from Kinshasa to Würzburg, the second is his return to Africa, during which he taught at the Kinshasa faculty of Catholic theology and at the Catholic University of Eastern Africa in Nairobi. The third is his teaching post at the University of Fribourg, Switzerland, of which he [served as Vice-Rector and retired as emeritus professor]. While the same issue marks these three stages, each of them formulates it differently and with new interlocutors. Events, men and cultures encountered, as well as the questions raised by the contemporary African situation widened his horizons to the point that the theology of the ‘Passionate for African man’, has become a truly contextual one, opened towards the universal.” – J. Ilunga Muya, “Benezet Bujo: The Awakening of a Systematic and Authentically African Thought”, in B. Bujo – J. Ilunga Muya (ed.), African Theology: The Contribution of the Pioneers, Paulines Publications Africa, Nairobi 2003, p107.

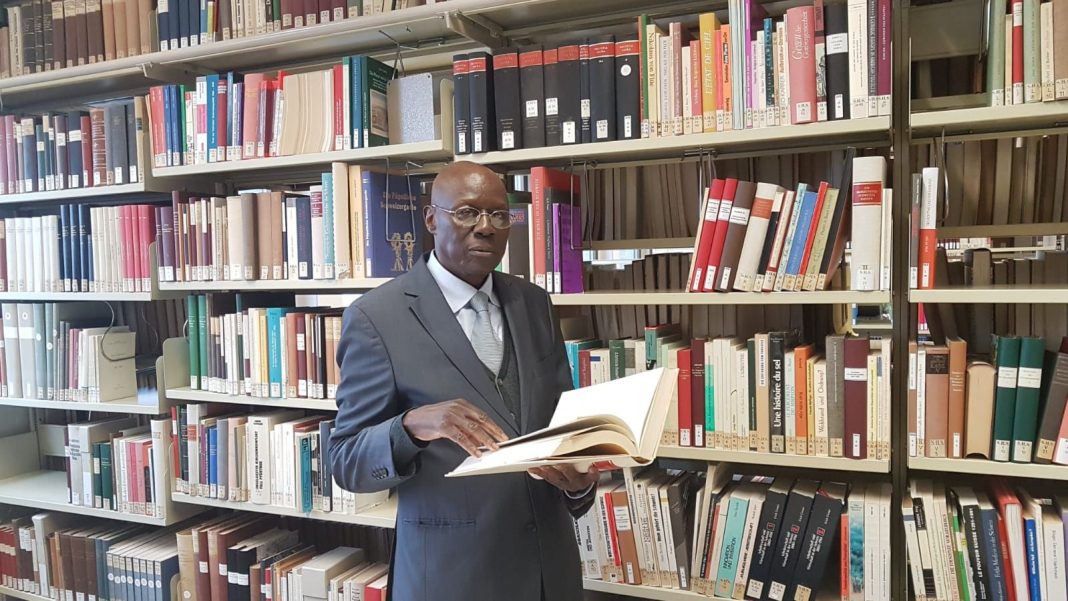

Africa is mourning! Professor Bènézet Bujo has been called to the great beyond, to the Risen Christ, his Merciful Redeemer and Savior, and to the communion of his African ancestors and other Saints of God in heaven! With his death, Africa mourns, once again, another of its giants, a trailblazer in African Christian theology. The continent has just lost to the cold hands of death, one of its foremost pioneers in the birth and development of the emergent systematic African theology, Rev. Father Professor Bénézet Bujo, from the Democratic Republic of Congo, DRC, who died at the age of 83.

It was a sad day! But at the same time, as Christians and Africans, it was a day of reaffirming our faith in the Risen Christ, the Merciful Redeemer and Savior of the world. That is, as believers in the Resurrection of the dead as taught us by Jesus Christ himself, ‘our Proto-Ancestor, the Ancestor par Excellence’. These are the Christological titles and qualities, Bujo, in his Systematic African theology, has ascribed to Jesus Christ, from an African perspective and thought-pattern.

Bénézet Bujo (1940-2023): Biographical Note

Born in 1940, in Drodro in the province of Ituri, in the Northwest of the Democratic Republic of Congo, Bénézet Bujo, at the time of his death, was professor emeritus of Moral theology, Social Ethics and African theology at the University of Fribourg, Switzerland. He died after a long illness on Thursday evening, November 9, 2023, at the Fribourg Cantonal (Regional) Hospital. According to an obituary published by the University of Fribourg on November 14, Rev. Father Professor Bujo taught numerous courses in Europe and Africa. He started his university teaching career early in life, in his own native country and in his alma mater Lovanium-Kinshasa Faculty of Theology, in DRC. From 1983 to 1988, Bénézet Bujo taught as a full professor at the Faculty of Catholic Theology (now Catholic University of Congo), Kinshasa, before being appointed as the German-speaking chairperson of moral theology, social ethics and African theology at the Faculty of Theology of the University of Fribourg, Switzerland. A position which he held until his retirement in 2010. After his retirement, he served as theological advisor to Caritas Africa for five years, from 2011 to 2015.

He was a visiting professor at the Catholic University of Eastern Africa, Nairobi and at the Faculty of Catholic Theology at Goethe University in Frankfurt am Main, Germany. He received invitations also from Lund, Johannesburg and Catholic University of Madagascar, Anatananarivo, among others.

Bénézet Bujo, did his primary and secondary school studies in his native town and province in DRC. He entered the Murhesa Major Seminary, Bukavu, and from there to Niangara (Isiro), where he studied philosophy and theology under the direction of the Dominican missionaries. Thereafter, he returned to Murhesa (Bukavu), to continue with his theology. He was then sent to the University Lovanium-Kinshasa in 1966 by his bishop, Msgr. Gabriel Ukec. He was ordained priest in 1967 for the diocese of Bunia. In 1969, Bujo obtained his theological Licentiate degree with the thesis, “Loi Ancienne, Loi Nouvelle et Loi Naturalle” (“Ancient Law, New Law and Natural Law”).

From this, it was clear, the brilliant, young African student of theology, Bujo, was being confronted with the fundamental question that interests his young inquisitive mind as an African: “Can the moral law be founded on something other than the natural law?” Bujo was being influenced, and inspired by his studies as a student at Lovanium, where the framework of Vatican Council II, specifically, the theology underlining the Pastoral Constitution, “Gaudium et Spes” and the publication of Pope St. Paul VI’s encyclical letter “Humanae Vitae” on 25th July 1968, were beginning to shape the theological thinking underway, especially, on Moral Theology, in the post-Council period of the day. “This raised the issue of the natural law, linked to the interpretation of Gaudium et Spes. How can one bind the conscience of people from other cultural milieus to an ethics founded on natural law?”

Bujo was not only a motivational university professor, mentor to both his colleagues in academia and students, but also a theological worker of the first hour. Apart from his major classical magisterial books, Bujo’s published articles and contributions to journals, volumes, encyclopedia and dictionaries of theology, are too numerous to mention. He has published several books of the highest quality and standard possible, especially, on inculturation of theology in the African context, in the areas of Christology, Ecclesiology, Christian Morality and Ethics, etc.

His major publications (books), include, his Magnus opus on African theology – the synthesis of his African theology, titled, “African Theology in Its Social Context” (Orbis Books, Maryknoll, New York 1992 (translated into several modern languages). His other books include: “African Christian Morality” (St. Paul Publications – Africa, Nairobi 1990); “Foundations of an African Ethic”, Herder & Herder, New York 2001. Here, Bujo made plea for a new model of marriage and sexuality). Among his other works are, “God Becomes Man in Black Africa” (Paulines Publications-Africa, Nairobi 1995); “The Ethical Dimension of Community: The African Model and the Dialogue Between North and South” (Paulines Publications – Africa, Nairobi 1998); “Introduction to African Theology”, published by Academic Press in Fribourg (2008; 2021); followed by a series of volumes on the great figures of African theology (published in several languages), with the title, “African Theology: The Contribution of the Pioneers” (Paulines Publications – Africa, Nairobi (Vol. 1 (2003), Vol. 2 (2006), Vol.3 (2013). Bujo co-edited the first two volumes with J. Ilunga Muya, and from volume 3, started to edit the series all alone).

Bujo’s Theological Background and Path of African Theology

The question of the interplay, of establishing some theological links between the moral law and the natural law as conceptualized in the Western thought and philosophy, in their relations to those of other cultural milieus (especially, non-European cultural milieus and thought-patterns), represented for our then young African theologian, Bujo, ‘a master of thought which succeeded, at the dawn of modern times, in synthesizing medieval thought with antiquity. But as some authors have rightly remarked, to understand Thomas Aquinas better one has to take him as a lighthouse, not as a port of arrival.”

Meeting, while in Germany, the great masters of contemporary exegesis like Rudolf Schenackenburg, and teachers of dogmatic theology like Karl Rahner, Edward Schillebeeckx, Johann-Baptist Metz and Walter Kasper, among others, has left its mark and influenced Bujo’s theological evolution. Moreover, reading the works of Thomas Aquinas and especially, “Summa Theologiae” (with the help of important contributions like Marie Dominque Chenu’s, Max Seckler’s and Otto Hermann Pesch’s), convinced him the more that theology must be understood as a whole.

For Bujo, through commentaries on biblical texts, Aquinas developed a whole method of doing theology rooted in symbols, analogy and metaphors, closer to the Fathers of the Church and to African thought. The importance of such a method becomes clearer to him through a meticulous analysis of Bonaventure as highlighted by Joseph Ratzinger’s “Die Geschichtstheologie des heilgen Bonaventura” (1959), and that joined on this point that of Thomas Aquinas on the biblical texts.

This centrality of the Word of God, which on meeting cultures causes the springing up of something totally new, will determine not only Bujo’s theology, but also his spirituality. “If it is true that enrichment and a reciprocal transformation results from every meeting, Christianity must not ignore African cultures”, Bujo argues.

In other words, Bujo saw St. Thomas Aquinas, then, as the author with whom to argue best the problem of the specificity of Christian morals. The question became therefore, “to know whether St. Thomas Aquinas’s philosophy (his reading of Aristotle) had not been modified by God’s Word: didn’t God’s allow him to re-question the philosophy received from Aristotle? What enrichment had occurred between his reading of the Word of God and Aristotle’s philosophical culture?” The dialogue with Thomas Aquinas’ theology was the occasion for showing the transformations and reciprocal changes occurring when the Gospel meets various cultures. Here, the challenge and relevance of Inculturation comes to the horizon. It would mark the whole of Bujo’s work.

This question and challenge dominated the core of Bujo’s doctoral thesis in 1977 at the University of Würzburg, Germany, which he entitled: “The Autonomy of Morals and the working out of norms in St. Thomas Aquinas.” This idea and theme, also, featured in his “Habilitation” (post-doctoral thesis) in moral theology in 1983, also in Würzburg.

Although, it is true that the two theses of doctorate and “Habilitation” (post-doctoral thesis) are about the moral conception of Thomas Aquinas, one can see there the concern already expressed in his licentiate thesis in Kinshasa, namely, ‘wanting to found morals on something other than natural law in view of a dialogue between Christianity and the non-European cultures. His first, programmatic works, essentially epistemological, try to lay the fundamental principles for a fruitful dialogue between the autonomy of morals, the biblical message and the Magisterium of the Church. “The question of autonomy is that of the individual conscience and its relation to all authority external to it, civil or religious. This question of moral autonomy versus heteronomy is fundamental for the drafting of norms.”

All these imply that Bujo’s epistemological works are intended to show that the autonomy of ethics is not simply philosophical construction, but a true demand of the Christian faith. This in turn, presupposes human freedom, itself founded on the creation of man in the image and likeness of God. In this perspective, “human morals cannot be conceived as compartmentalized, with a first level of natural efforts followed by a Christian addition at a superior level.” To accept the principle of moral autonomy means to stop opposing human natural intelligence to the Christian faith. (See B. Bujo, African Christian Morality, St. Paul Publications – Africa, Nairobi 1995, p.36f.)

Furthermore, Bujo argues that understanding the Magisterium of the Church is linked to this conclusion. “Accepting the principle of human autonomy entails a number of consequences in the exercise of the Magisterium: to give up pretending to be the sole guardian of moral truth; to develop a new conception of power not as brute strength but as communion of Christian charity; giving up pretending to be the possessor of the only philosophy valid for all and let the Gospel create new philosophies in contact with various cultures, with novelties within Christianity itself, and with new cultures met with.”

It suffices to add, that the method of Bujo’s theological work can be deduced from this paragraph, cited above. It is inspired in St. Thomas Aquinas and it is fundamentally biblical and in the form of dialogue. As J. Ilunga Muya (Bujo’s most trusted biographer), opines, “It is biblical because it lays the foundation, like Thomas Aquinas, the spiritual experience that springs from the reading of the Bible and at the same time it is “dialogue” in community perspective.” It takes the community (not nature or being) contemplated in its visible and invisible dimensions, as destined to communicate life, as the center about which everything revolves.

Furthermore, the method does not place at its origin a dualism ‘matter-spirit, profane-sacred, natural-supernatural, transcendental-immanence, interior-exterior.’ But rather, it is an integration, an original unity maintaining differences, while always presupposing correlations. In the opinion of Bujo, this perspective is found in “nuce” already in St. Thomas Aquinas. And Bujo will fundamentally determine it for African culture.

This methodological orientation also determines Bujo’s style, more down to earth than that of theologians who have decided to dwell in idealistic neo-Scholastic abstractions, or in a nostalgic cultural folklore or in an African traditionalism far removed from contemporary African reality. “His being rooted in African tradition, for him, is no longer going back to a ghetto (or turning within oneself), but deep dialogue with the contemporary African context and of what is best that can be taken from the great Western philosophical and theological trends.” – (See J. Ilunga Muya, “Benezet Bujo: The Awakening of a Systematic and Authentically African Thought”, in B. Bujo – J. Ilunga Muya (ed.), African Theology: The Contribution of the Pioneers, 107-149).

Major Aspects of Bujo’s African Inculturation of Christian Theology

As I discussed in chapter four of my book, “Trends in African Theology Since Vatican II” (1998), Bénézet Bujo and Charles Nyamiti are regarded as the two great advocates of Inculturation of Christian theology in Africa, in the area of Christology. A careful study of their respective writings and those of others, reveal that, of all the theological themes, Christology (in particular, “Ancestorship” model of Christology) has received the greatest attention of the African authors. It is the focal point from which various theological themes are being addressed by the theologians. This is in line with African tradition where one could speak only of “wholeness in life”, and religion (African Traditional Religion) as the unifying principle, both of African culture and of world-view. Hence, the theologians, in their reflections, rightly observe that one cannot speak of any aspect of the Africa’s religious life or culture without touching the whole of the African world-view and life. And that it is difficult to speak of one aspect of African theology without in one way or the other touching other aspects or themes as well.

Moreover, in Christian religion, the person of Jesus Christ is at the center or rather the determining factor of theological evaluation. This fact should apply as well to African Christian theology. For the theologians themselves, say, ‘Christology is the focus of Christian faith; thus … the most understandable symbol of redemption in Christian theology.’ It goes to show the reason why the question – “Who is Christ for the African?” has recently become the principal pre-occupation of the theologians. African Inculturation Christology, when compared to other efforts, it is more widespread, more developed, and exhibits more originality and variety of methods. (See, C. Nyamiti, “Contemporary African Christologies: Assessment and Practical Suggestions”, in R. GIBELLINI (ed.), Paths of African Theology, SCM Press, London 1994, pp.64-65).

Secondly, there are those among the theologians, who attempt to construct an African Christology by starting from the Biblical teaching about Christ and strive afterwards to find from the African cultural situation the relevant Christological themes. Authors of this school attempt also at establishing a kind of continuity between the God worshipped in African Traditional Religion (ATR) and the God in the Bible, and therefore of Christ. In this camp are also those who apply to Christ qualities or titles in relation to his “functional”, or existential deeds as a Galilean villager. In this respect the authors of this school share a lot in common with African Liberation theologians (a theme which I treated in chapter 6 of my book, “Trends in African Theology Since Vatican II.”) Stress is put on the historical background and biblical texts concerning the man Jesus of Nazareth; especially his mission to fight against poverty, hunger, disease, ignorance, oppression or subjection of the people and denial of freedom. Most of the Protestant African Christologists belong to this school of thought. (See, J. PARRATT, Reinventing Christianity: African Theology Today, WM. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, Grand Rapids, pp.81ff).

This leads us to a brief presentation of the following three main aspects of Bujo’s attempt at developing an African Inculturation theology in the three areas of a) Christology; b) Ecclesiology; and c) Christian Morality.

- Bujo’s Christology

Bujo’s Christology is securely rooted in the traditional concept of the ancestors in the African context, and at the same time seems to have consequences for morality (ethical life of the community) and for ecclesiology (the organizational structure of the community). Bujo attributes to Christ the title of “Ancestor Par Excellence”, that is of “Proto-Ancestor” in whom the whole life of the African Christian can be rooted. To arrive at this title Bujo does not place Christ the Ancestor at the level of biological lineage (as Nyamiti did), as if Christ is just one of the ordinary human ancestors, that is, at the level of consanguinity. Rather Christ the Ancestor is of the transcendental level. It is from this perspective that Bujo chooses to speak only of good ancestors, who are regarded as God-fearing and who, through their activities, can exercise a good influence on their descendants, by showing how the force which is life is to be used as God wishes it to be used. Hence, Bujo avoids those ancestors whose activities after death spread fear and anxiety rather than love among the living. (See, B. BUJO, African Theology in Its Social Context, 79.)

Of particular importance to Bujo are the last words of a dying person, especially of a father or mother. For him, these words are an abiding rule of life, a rule that must be repossessed by the living, for upon them depend their welfare and wholeness (Heil). Bujo observes that the ancestral veneration on the part of living Africans is no mere secular exercise. It must be understood as part of the general framework of ancestor respect and therefore as religious. Therefore, for our author, the gestures of the ancestors enacted through rituals and the African’s effort to conform his conduct to his ancestors’ experiences are life-and-death rule of conduct, guarantors of salvation, and a testament for posterity. (See, B. BUJO, “A Christocentric ethic for black Africa”, in: Theology Digest, 2(1982)30, p.143.)

It is from this context that Bujo reflects on the mystery of Christ, whom, as we noted already, he sees as the “Ancestor Par Excellence”, the “Proto-Ancestor”, that is, the “Unique Ancestor” who is the source of life and the highest model of all Ancestorship. His view is that it is meaningful to speak of Jesus as Ancestor Par Excellence, for in him are fulfilled all the qualities and virtues that the African ascribes to his or her ancestors. In other words, the historical Jesus fulfills the highest ideals ascribed to the ancestors in African thought – he heals, he cures, he raises the dead, and so on. In short, he imparts life force in all its fullness. This love and power he bequeaths, after death, to his disciples. It is precisely in his death and resurrection, with its soteriological meaning, that Jesus transcends the ancestors. This is a Christology from below and provides a point of departure for a Christology in the African context. (See, B. BUJO, African Theology in Its Social Context, p.80.)

Bujo is convinced that the idea of Christ as Proto-Ancestor – besides being more meaningful (than for example, logos or kyrios) to the African makes it possible for African anthropocentrism (prominent in ancestral thinking) to be the source for incarnating Christianity. This demands – in Bujo’s view, an ascending Christology, or rather a Christology from below showing that – being wholly African and authentically Christian are not incompatibles.

Our author notes further that the idea of Christ as Proto-Ancestor is basically Trinitarian. The relationship between the Father and the Son may be seen as one of mutual interaction and sharing of life; in African terms it is a bond of vital union, life force, or divine power. Understood in terms of traditional theology, it is a bond of the Holy Spirit. This divine life of the Spirit is conveyed by the Proto-Ancestor to the community. In Bujo’s view, the community also includes the ancestors themselves, for Jesus, in his work of bringing to completion and fullness the whole of the created universe also brings the ancestors into this fullness of life. Another Christological model that has been favored by contemporary African theologians, that of Christ as the Master of initiation, formulated by Anselme T. Sanon, also rests, in Bujo’s view, ultimately on the ancestor concept. For the powers of initiation and the life force conveyed through this rite ultimately depend for their efficacy upon the ancestors. (See, B. BUJO, African Theology in Its Social Context, p.86.)

-

Bujo’s Ecclesiology

Bujo argues further, that the Ancestorship Christology as he presented it, has consequences for ecclesiology: for just as Christ can not be separated from his Church, the ancestor or clan founder can not as well be separated from his descendants. From this background, Bujo proposes a Christological-Eucharistic Ecclesiology, oriented towards the African concept of life. Bujo begins his thesis by examining the significance of Jesus as life-giver, a central theme in the New Testament, especially in Pauline theology. For Paul draws a parallel between the first and second Adam (cf.1 Cor 15,45ff; Rom 5,12ff), and speaks of Christ as the First-born from the death, as the Head of the body, the Church (Col 1,8; 1,15), as the first fruits of those who have fallen asleep (1 Cor 15,20). In him resides the fullness of God, who has chosen to use him to reconcile all things (Col 1,19-20).

In addition to the Pauline teaching on Jesus as the head of creation, Bujo makes reference to the concept of life in the Gospel of John. In John, Jesus is presented as one who has come so that his followers may have life and have it in abundance (John 10,10). He gives his life for the sheep (John 10,11-15). Jesus is the true vine, and we can only bear fruit when we remain attached to him (John 15,1-6). Even more, Jesus is the resurrection, and the one who lives in him and believes in him will never die (John11,25-26). This implies that the exalted Jesus is the means through which God imparts his divine life to the world; he is, as it were, the Bread of Life, the source of eternal life (John 6,32-58) and therefore the proto-life source. (B.BUJO, African Theology in Its Social Context, p.93.)

It is from this context that Bujo describes the Church as the focal point from which the life of the proto-ancestor flows and spreads to all humanity. He notes also that the Eucharist is not simply an object of contemplation. But rather is the very life of the Church and the source of its growth; life that is not merely biological generation, but rather mystical and spiritual. Seen in this light, the Eucharist, as the “ancestral meal” instituted by the proto-ancestor, stands at the heart of African ecclesiology. The purpose of the Eucharist (as with some African death ritual) is to impart life in all its fullness for the welfare of the whole community. This life is the Spirit. Once more, Bujo returns to the claim that the ancestral model is Trinitarian, in that Father, Son, and Spirit are the source, imparter, and substance respectively of the divine life in the community.

Finally, Bujo adds that an ecclesiology based on such an ancestral model presents a number of challenges to the life of the Church. For in the traditional society each member is expected to make his or her contributions to the vital force of the whole community. In this regard, Bujo chooses to address the behavior of those within the inner life of the Church. The life force that finds its source in God and in the ancestors is dependent for its efficacy in real life upon the actions of the members of the earthly “body”. So within the Church, each member (from bishops, priests, religious, seminarians, down to the laity) has a role to play in transforming the conditions of postcolonial Africa by contributing to the divine life force of the whole. Members of the Church can do this effectively if the individual’s lifestyle (especially among the clergy) is seen to be exemplary in the community. Once more, Bujo notes that the source for the active role of the individual Christian in the community, is the severely practical outworking of the fullness of life imparted by Jesus as proto-ancestor. This is as rooted in the religious experience of the ancestors, and in the Biblical concept of the word of life, who brings life to his people and leads them through the Spirit into the fellowship with the Father. Thus, Bujo concludes that an ecclesiology based on the model of Jesus as Proto-Ancestor will be able to relate in a meaningful way to Africans of today. (B. BUJO, African Theology in Its Social Context, p. 96f.)

-

Bujo on African Inculturation of Christian Morality

According to Bujo, the idea of Christ as Proto-Ancestor can be the foundation for ethics and practical behavior in present-day Africa. For “if Christ is Proto-Ancestor, source of life and fulfilment, our human conduct must model itself on, re-enact the memory of his Passion, Death and Resurrection. Such ethic demands personal assimilation of the experiences memorialized in Christ’s paschal mystery. In other words, virtues shown in this mystery “must become part of our lives”. (See, B. BUJO, African Christian Morality at the Age of Inculturation, St. Paul Publications-Africa, Nairobi, 1990, pp.103ff.)

Bujo adds that this Christocentric ethic “confirms the positive elements of African anthropocentrism”, such as hospitality, family spirit, solicitude for parents, and so forth. But it also corrects and completes African traditional and modern customs. For the Christ-event is “… both memoria liberationis and subversionis, both liberating and subversive – both humanizing and purifying for black Africa ethos”. It judges African tradition as well as exposing the colonial sins of inhumanity, oppression, and the post-colonial abuse of power and corruption. This implies, in the opinion of Bujo that the modern African can only tread in the footsteps of Jesus Christ when he sees him not as a tyrannical kyrios, but rather as proto-ancestor, whose legacy is an appeal to his posterity to toil unremittingly to overcome all inhumanity, and to liberate, purify and humanize African culture. This is the basis of an ethic for Africa today that will bring the ancestral ethos into dialogue with the Christian faith. The foundation of this is from the fact that for an African, there is no dichotomy between private, social, political and religious life. Hence, Bujo argues that an ancestral model of morality must permeate the whole of Christian life. He works out the practical aspect of this theory through what he calls an African spirituality for problems of marriage and care for the dying. (See, B. BUJO, African Theology in Its Social Context, pp. 90-92; Idem, African Christian Morality at the Age of Inculturation, p.78.)

Of particular importance to Bujo is the subject of “trial marriages” which, according to him, still creates major problem in some African ethnic-groups. The reason for this is that, in African society, the achievement of life, as commanded by the ancestors, is an affair of the whole community. In traditional African society, a man who dies childless falls into oblivion. Such a person will be unable to find happiness in the next world because, having no children to honor him, he is cut off from the family community. Furthermore, childlessness is a personal disgrace. It is also felt as a kind of slur on the community, a social fault, and it often leads to divorce or polygamy. This is why many African families expect their members to enter marriage on a provisional basis until the wife’s ability to bear children has been established. For experience has shown that a marriage which has been validly celebrated in Church, but without regard to the traditional customs, is essentially fragile, especially if it remains childless. (See, B. BUJO, African Theology in Its Social Context, pp.115-116.)

Bujo does not agree with the solution some theologians offered to this problem. Some theologians have asked that Church discipline be relaxed so that African partners may live together before marriage. Some others proposed that the African view of marriage be extended to the universal Church, so that infertility would be everywhere an impediment to valid Christian marriage. However, on his own part, Bujo asks for dialogue between African ethnic-groups with different marriage traditions, since this impasse has already been overcome by some. In that respect, a common ground can be found on the ancestor theology. Everywhere the African ethnic-groups revere their ancestors. Hence, an ancestor spirituality would be a great help to an African in the moral problems of marriage and of daily life.

In this context, Bujo calls on Africans to turn to Jesus Christ, the Proto-Ancestor, and find him a model of dedication to the community, unfailingly on the side of the weak and despised. These were the ones with whom Jesus identified Himself, becoming one with them so that all might share in the glory of God. Therefore, in keeping with the fundamental intention of the ancestors, African Christians are to make the narration of the story of Jesus, the memory of his Passion, Death and Resurrection into criteria of African ethics and spirituality. In this sense, when they bring their marriage problems to Jesus, they can see at once that African attitudes must change, especially the attitudes of African men. So that a barren wife is accepted and treated with love, for she is numbered among the weak who were dear to Jesus. Moreover, she enjoys the fullness of life which flows from the Proto-Ancestor, and therefore should not be treated simply as a bearer of children. She has worth in herself, as a child of God and a kinswoman of Jesus. Bujo notes that the same attitude should be extended to the care of the dying in the African context. (B. BUJO, African Theology in Its Social Context, pp.121ff.)

In Conclusion

Critics of Ancestral Christology point out that such a model runs the risk of reducing almost all moral issues and understanding of the Mystery of our faith in Jesus Christ, to ancestral memorial. It is dangerous to reduce wholesale the African daily life as a re-living of the life of dead ancestors. Especially, if we are to consider the momentum of the process of modernization, urbanization and universalization of education has gathered today.

Be that as it may, Bujo’s concept of proto-ancestor, has been hailed by many theologians, Africans and non-Africans alike. Theologians see it as a more appropriate paradigm to interpret Jesus Christ, his salvific functions and his relationship to the Church and humanity, than simply the traditional concepts of ancestor, healer, and chief in the African context. In other words, one cannot deny the usefulness, relevance of inculturating Christology in the cultures of Africa. There is an immense catechetical value in the whole attempt at presenting Jesus Christ in terms of African culture, thought-pattern and philosophy.

It is in this regard that Bénézet Bujo has made the greatest contribution of his Christian witness as a theologian and African, to the Church’s evangelizing mission in Africa, in the area of inculturation of the Christian Message in the continent and the world at large.

Adieu, our great theologian, teacher and professor, Rev. Father Professor Bénézet Bujo. May the Angels of God open the Gate of Heaven for you! May you rest in the bosom of the Risen Christ, your ‘Ancestor par Excellence, Proto-Ancestor’, the Merciful and Eternal Redeemer!

May the Heavenly Communion of our African Ancestors and Other Saints in Heaven, accompany you as you go before us, marked with the sign of faith to meet the Risen Christ, and to receive the reward of your meritorious and model Christian witness of life as a theologian and teacher of the Christian Mystery. As you reach there, send our greetings to other great African theologians, your colleagues, recently called to the glory of God in the great beyond. May you all continue to intercede for your African people, continent, Church, humanity and the world!

Rest in peace, Rev. Father Professor Bénézet Bujo, the great protagonist of African Ancestorship Christology and Inculturation of Christian Morality and Ecclesiology in Africa! Adieu!

Francis Anekwe Oborji is a Roman Catholic Priest. He lives in Rome where he is a Professor of missiology (mission theology) in a Pontifical University. He runs a column on The Trent. He can be reached by email HERE.

The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author.