Michelle Knight smacks a red punch bag that is almost as big as her. Biff. Biffbiff. Biffbiffbiff. Her punches are getting faster and harder. Does she ever think of him when she’s punching, I ask. Yes, she says. Biffbiffbiffbiff. “When I got out and started seeing him on TV, I just wanted to put his face right here, and hit it. So I took the paper and you can tell – the dent’s right there.” She never uses his name, but “he” is Ariel Castro, the school bus driver who kidnapped her, held her hostage in his house in Cleveland, Ohio, for 11 years, made her pregnant five times and beat her into miscarrying five times.

Knight escaped one year ago this week, alongside two other young women, Amanda Berry and Gina DeJesus. Castro pleaded guilty to 937 charges, including aggravated murder, kidnap, rape and assault, and last August was given a sentence of life plus 1,000 years. As for Knight, she is starting to rebuild her life. And, boy, is there some rebuilding to do. Her sight is weak from years in darkness, her stomach permanently damaged from a combination of infections and Castro’s beatings; she has psychological and trust issues, and has cut herself off from the family she says never bothered looking for her. Her existence these days is largely solitary. Perhaps the miracle is that she survived at all.

Before Castro’s sentencing on 1 August, Knight stood in court and read a heart-wrenching statement that not only detailed what he had done to her but stretched out a hand of forgiveness. Tiny (she is 4ft 7in), bespectacled and tearful, she said: “Good afternoon. My name is Michelle Knight. And I would like to tell you what 11 years was like for me. I missed my son every day. Iwondered if I was ever going to see him again. He was only two-and-a-half years old when I was taken… Days turned into nights. Nights turned into days. The years turned into eternity.”

Castro sat behind her in his orange prison uniform as she spoke about how he had tried to destroy his three victims. “I spent 11 years in hell, and now your hell is just beginning. I will overcome all this that happened, but you will face hell for eternity. From this moment on, I will not let you define me or affect who I am… I can forgive you, but I will never forget.” Castro was found hanged in his cell a month later.

Back in her flat in Cleveland, Knight punches her bag. She boxed when she was a little girl – she would throw punches at a log wrapped in a pillow – and hopes to compete in the ring, but she no longer pictures Castro when she fights. “I took his picture down after I faced him in court. I felt relieved because then I didn’t have to feel that monster’s eyes beaming on me any more.”

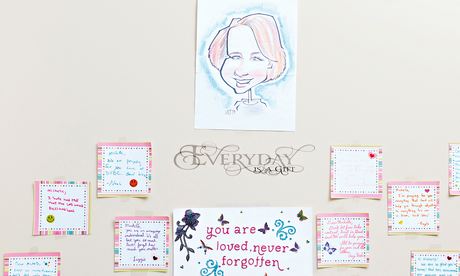

Her living room is lit up with the early spring sunshine. One wall is covered with messages of love and faith from local schoolchildren. Next to the punch bag, there is a basketball hoop and a micro-sized pool table – a mini indoor sports area. It is Knight’s birthday today (she is 33), and there is a helium balloon hanging from the ceiling, and cake on the kitchen table. “It’s the first time I’ve had a balloon that says Happy Birthday, or flowers, or cards. This is like my first birthday ever.”

Knight has written a gruelling book, Finding Me, about her experience, in which she never once mentions Castro by name. He is always “the dude”. (He doesn’t deserve a name, she explains. “He hated the fact that I called him dude, because I didn’t acknowledge him as a person.”) Why did she write the book? “I wanted everyone to understand that when you go through hard times, you can actually make it through. You don’t have to let the darkness swallow you.” She has a lovely, slow, sing-song voice – not unlike Sissy Spacek’s Holly in the film Badlands. Did she ever think the darkness would swallow her? “No, I knew I would overcome it.” But this is Knight at her most positive. Ask her another time, and she will admit there were plenty of moments when she wanted to die.

Sheriff’s deputies guard Ariel Castro’s Cleveland, Ohio house last May. Photograph: Tony Dejak/APOn 22 August 2002, Knight had been due to attend a social services meeting to discuss custody of her young son, Joey. She was late, and in a panic. She went to a convenience store to ask for directions. Castro overheard her and said he could give her a lift. She recognised him as the father of a younger girl who had attended her school. “I looked at him, and said, ‘I think I know you – your daughter’s name is Emily, right?’ And he was like, ‘It’s a small world after all.’ He didn’t strike me as a bad person at first. He struck me as a good person.”

Sheriff’s deputies guard Ariel Castro’s Cleveland, Ohio house last May. Photograph: Tony Dejak/APOn 22 August 2002, Knight had been due to attend a social services meeting to discuss custody of her young son, Joey. She was late, and in a panic. She went to a convenience store to ask for directions. Castro overheard her and said he could give her a lift. She recognised him as the father of a younger girl who had attended her school. “I looked at him, and said, ‘I think I know you – your daughter’s name is Emily, right?’ And he was like, ‘It’s a small world after all.’ He didn’t strike me as a bad person at first. He struck me as a good person.”

There was a note stuck on his car advertising puppies for sale. She told him Joey liked puppies. “He started the car, and the first thing he did was a huge spin in the car park. I’m like, ‘Seriously? Really?’ And he’s like, ‘Oh, my kids love it when I do that.’ So I excused it, which I shouldn’t have. Because that was one of the signs I look back on, and I think I should have got out of his car. The only thing is, if I’d tried, there was no door handle.” Knight was 21 at the time, but looked many years younger.

She noticed he was driving the wrong way. When she asked why, he said he was popping into his house, and that he would give her a puppy for Joey. “So he pulls in. He came into the driveway and locked the gate to the yard. I’d never seen anybody lock their gate, and he said it’s because it’s a really bad neighbourhood. So I thought, OK. After we pull in, we go into the house and he turns around and he locks his door. Then he’s like, ‘The puppies are upstairs.’ As I get close to the stairs, I notice I don’t hear puppies. I asked him why – puppies are noisy. He said, ‘They’re taking a nap.’ I get up to the second floor, and I think, I ain’t ever getting out of here. I had a cracking feeling in my heart. As I got closer, I started to shake. He noticed, and said, ‘You don’t have to be worried’, but my body was telling me something different. There’s something wrong here, and it was already too late. Either I was going to die or he was going to do something to me, that’s all I could think. Then, when he shut the door on me, I knew it was over. It was just over. I was not getting out of that house, ever.”

The suburb of Tremont is now a trendy part of town, known for its restaurants and art galleries. But there is nothing desirable about Seymour Avenue. Last year, Cleveland was named one of America’s 10 most dangerous cities, and property here is still cheap: in 2012, Castro’s white clapboard house with its boarded-up windows was valued at $36,100.

I make the journey from the house where Knight was living with her cousin in 2002, to the store where she met Castro, and then on to his house: it takes a couple of minutes in traffic. For those 11 years, she was only a couple of blocks from home.

2207 Seymour Avenue was demolished on 7 August 2013, six days after Knight gave her statement to court. She was there to see it knocked down, giving out yellow balloons to neighbours as symbols of the world’s missing children. (DeJesus and Berry stayed away, and did not attend court.) In its place there is a square of grass and a long bed of soil that will hopefully flower one day. The tree-lined avenue is quietly hostile; there are signs on the houses either side of Castro’s wasteland, warning off trespassers. I lift up the soil and smell it. The sun is shining bright, it is silent but for birdsong, and I’m thinking that for all those years Knight, Berry and DeJesus were locked in Castro’s cellar, underneath this soil.

Knight with her friend Mitchell, recording a charity single. Photograph: Christopher Lane for the GuardianThe next day we head to Cleveland’s Magnetic North Studio, where Knight is recording a charity single with her 16-year-old friend, Mitchell. The taxi driver, Will, like every cabbie I meet in Cleveland, is keen to talk about Castro and his captives. He tells me that he was friends with the father of Gina DeJesus and would regularly go out looking for her. He passed Castro’s house every day. “I didn’t have a clue. Can you imagine? Every day I drove past.” He is beating himself up about it. “You know, Castro was in a band. I actually went to see them play.” It comes out like a confession. “They were pretty good. He played bass guitar.” You sense the city shares a kind of collective guilt.

Knight with her friend Mitchell, recording a charity single. Photograph: Christopher Lane for the GuardianThe next day we head to Cleveland’s Magnetic North Studio, where Knight is recording a charity single with her 16-year-old friend, Mitchell. The taxi driver, Will, like every cabbie I meet in Cleveland, is keen to talk about Castro and his captives. He tells me that he was friends with the father of Gina DeJesus and would regularly go out looking for her. He passed Castro’s house every day. “I didn’t have a clue. Can you imagine? Every day I drove past.” He is beating himself up about it. “You know, Castro was in a band. I actually went to see them play.” It comes out like a confession. “They were pretty good. He played bass guitar.” You sense the city shares a kind of collective guilt.

Knight has a cold but is doing her best in the studio. As she sings, I chat with Peggy Foley Jones, her lawyer. Jones is a former judge whose own sister was raped and murdered in her early 30s, decades ago. She thinks this is why she took on Knight’s case. Since then, she has become much more than a lawyer to her. Jones says Knight has changed hugely in the past months – last summer, you could hardly get a smile out of her – but she can see problems ahead, and worries that Knight is getting involved with the wrong people. “Since Michelle came out of the house, it’s been a whirlwind for her. I worry what her life will be like after this. She’s pretty much a celebrity now, and when the book’s over, she might well not be.”

Jones tells me about the effect the kidnappings have had on Cleveland. It’s not the city’s only recent trauma. She tells me that between June 2007 and July 2009, on the other side of town, a man called Anthony Sowell raped and strangled 11 women, most of them recovering or current drug addicts. So the city is suffering a double guilt. Recently, Jones was out with Knight when a stranger approached them and addressed Knight. “I recognise you. You are Gina DeJesus,” he said. Jones takes up the story. “Michelle said, ‘No, I’m Michelle Knight. But I recognise you, too. Your picture was on the mantelpiece in his house.’ He then burst out crying, said that he was the sound technician for Castro’s band and had visited the house five times, and swore he knew nothing of what was going on.” Another time, she and Knight were in a restaurant when the waitress told them the meal was on the house and presented her with a fluffy toy rabbit. “She was also in tears. She said she was friendly with Amanda’s mother and went out looking for Amanda every Sunday.” After Berry had been missing for three years, her mother died – from a broken heart, Jones says.

In the recording studio, Michelle and Mitchell make for an odd couple. He is tall, gangly and serious, with a face straight out of a Norman Rockwellpainting; she is small, rounded and giggly. They met at a fundraiser, where he told her he had written a song that he thought she might like. He had read how much she loved music, how important it had been. Castro gave her a battered radio, and she did her best to keep it going. She adores hip-hop (Drake is her idol) but Castro, who was mixed race, hated her playing “black” music. Did she ever ask him what difference it made? “There was a time. Then I got punched in the face, and I’ve still got the scar.” She shows me – just under her lip.

When Knight came out of captivity, her jaw was so badly damaged that she slurred her speech. Now she speaks more clearly. For six months after her release, she lived in sheltered accommodation where most of the residents were elderly. Today she lives in a beautiful one-bedroom apartment in the smart bit of Tremont, where she can afford the rent because of her substantial book advance and various trusts that have been established for her.

There are birthday cards all over the kitchen table. How would she have celebrated last year? “In a room with Gina. We would have a candy bar and we’d sing Happy Birthday to each other, and we’d blow out a candle we were holding in our hand or that we actually tried to stuff on to the candy bar, which was incredibly hard. The same with Amanda, but she would sometimes get a cake. We would try to celebrate the best we could. We’d write each other cards.”

Knight and her lawyer Peggy Jones have become close. ‘She taught me how to dance,’ Jones says. Knight is laughing so much that she can barely get the words out. ‘She looked as if she was having a seizure.’ Photograph: Christopher Lane for the GuardianCastro kidnapped Berry a year after he took Knight, one day before Berry’s 17th birthday. A year later he kidnapped 14-year-old Gina DeJesus. (Knight is convinced she was kidnapped only because Castro thought she was far younger than 21.) Was there any comfort in knowing there were other girls in the house? Yes, she says, but her overwhelming feeling was pity. “I felt they didn’t deserve to be here. I didn’t deserve to be here. Everything that happened from that day was just going to be a big old mess. It’s a tragedy because you know exactly what she’s going to go through, and she ain’t going to like it. And you don’t know how she will react to it.” All three girls had known Castro’s children.

Knight and her lawyer Peggy Jones have become close. ‘She taught me how to dance,’ Jones says. Knight is laughing so much that she can barely get the words out. ‘She looked as if she was having a seizure.’ Photograph: Christopher Lane for the GuardianCastro kidnapped Berry a year after he took Knight, one day before Berry’s 17th birthday. A year later he kidnapped 14-year-old Gina DeJesus. (Knight is convinced she was kidnapped only because Castro thought she was far younger than 21.) Was there any comfort in knowing there were other girls in the house? Yes, she says, but her overwhelming feeling was pity. “I felt they didn’t deserve to be here. I didn’t deserve to be here. Everything that happened from that day was just going to be a big old mess. It’s a tragedy because you know exactly what she’s going to go through, and she ain’t going to like it. And you don’t know how she will react to it.” All three girls had known Castro’s children.

In their decade together, she and DeJesus built up a remarkable relationship, with Knight fulfilling a maternal role. For most of the time, the two girls were either shackled or locked in a dark room together. (Berry was given her own room, which she later shared with her daughter.) DeJesus and Knight listened to music together, read together, ate together, went to the bathroom together (a plastic toilet that was emptied infrequently). They had no choice. They looked out for each other when they were feeling ill, gave each other hope, talked about a future that they had to believe was possible.

Even the food she received was worse than the others’. She talks about the time she first met DeJesus, who had been told by Castro to take her a meal. “It was Chinese chicken. I hate Chinese chicken, especially the way he got it. Yep. It wasn’t tasty. He would wait at least a week or two till he handed it to me. It was whatever the others didn’t finish. After a while I noticed they got more and better food than me, and most of the time it was fresh.”

Did he ever show her kindness? She talks about the time he bought her a dog, and her eyes well up. “I loved the dog with all my heart. I cherished it. I named it Lobo. I thought, this is going to be amazing. I have somebody I can take care of.”

A few weeks later, Castro attacked Knight in front of Lobo. “So my dog bit him, and he got hold of Lobo by his neck and then just… [She makes a snapping gesture with her hands]… right in front of me. Then he went downstairs and got a bag to put him in, and threw it in the garbage bin like it was trash.”

I find myself confusing her captivity with prison. She doesn’t notice. “Is it true you were made pregnant five times when you were in prison?”

She nods, barely able to speak. “Yes.”

“And you wanted those babies?” “Yes. Not under any circumstances would I kill a child like that. No matter what I went through.”

Did you always know when you were pregnant? “Yes, it would be that amazing feeling I felt when I had my son. It felt like heaven was in my stomach. You could feel this big tickle. It’s just a feeling that overwhelms you with joy.”

What is the longest you were pregnant?

“Three months.” Silence.

A wall in Knight’s flat with messages of love from local school children. Photograph: Christopher Lane for the GuardianThe question I keep asking Knight is how she kept going. She says she tried not to wake up in the mornings. She wouldn’t get up until Castro bullied her out of bed. “I felt that me living in that house, everything was frozen. The only thing moving was the outside world. There was no reason to wake up, no reason to talk.” Often she’d pretend to be asleep. He constantly taunted her: about her looks, about the fact that nobody was looking for her.

A wall in Knight’s flat with messages of love from local school children. Photograph: Christopher Lane for the GuardianThe question I keep asking Knight is how she kept going. She says she tried not to wake up in the mornings. She wouldn’t get up until Castro bullied her out of bed. “I felt that me living in that house, everything was frozen. The only thing moving was the outside world. There was no reason to wake up, no reason to talk.” Often she’d pretend to be asleep. He constantly taunted her: about her looks, about the fact that nobody was looking for her.

She was convinced she would die in the house. Knight is allergic to mustard and, knowing this, Castro forced her to eat a hot dog coated in the stuff. Her face blew up and she couldn’t breathe. “I’m just sitting there asking God, ‘Is there a reason to go on living?’ There was a point when I told Gina, ‘Just kill me. Just put the pillow over my head and kill me. Let me go.’ She said, ‘I would, but I can’t because you’re my friend and I can’t let you do that.'” Another time, she says, she returned the favour. “Gina drank a little too much liquor and she wanted me to let her throw up and choke on it, and I couldn’t do it. I told her, ‘Either you’re going to get up or I’m going to come up and pick you up and make you go to the toilet.’ ” Knight grins her way through this grim story. “She was a dead weight, and I just tried my best.”

She admits her relationship with Berry was difficult: they had different backgrounds, different expectations of life. But even then, she helped deliver Berry’s baby Jocelyn (Castro said he would kill her if the baby did not survive) and talks of her love for the girl. “The child did bring happiness into the house. Life was worth living and waking up in the morning just to see that little girl smile, to see her play.” Castro would not allow Knight to call the baby by her name. “I called her Pretty, that’s all I was allowed.”

DeJesus and Berry used to tell her that she dealt with captivity unbelievably well. “They thought I didn’t have as many problems coping.” In the end, Knight says, her tough childhood helped her. She was brought up by a mother she says never cared about her, and who kept her away from school so she could claim welfare benefits. She was sexually abused from the age of five. When she did go to school, she was bullied. “There were times when kids would lock me in a locker,” she tells me later. “When I was 10, one kid put my hand in a locker and smushed it and said, ‘Now you’ll never be able to play basketball again.’ It broke my thumb and my wrist.”

In her teens she ran away, and lived on wasteland under a bridge. She stole a wheelie bin and made it her home. “I had my own little room, I didn’t need to share it with anybody. I didn’t have to hear my mother yelling, I didn’t have to hear glasses breaking, things being thrown at the wall. If I wanted to sing, I didn’t have to listen to my mum saying, ‘You’re a horrible singer, shut up.’ ”

Has she ever thought what would have become of her if she hadn’t been kidnapped? “I’d probably be living on a street or dead by now. It probably would have been drugs or drink.” So the hell she lived through might have saved her? She smiles. “Yes. Because it gave me street smarts. It made me see the other side of the road that no one else gets to see. Even though it was painful and horrible, I survived it.”

I ask whether she ever tried to make sense of what Castro was doing. Yes, she says, he considered the girls a surrogate family. If they were family, what was their relationship to him? “Wives,” she says simply. He would tell them he wanted them to be happy. In court, he said: “I hope they can find it in their hearts to forgive me because we had a lot of harmony going on in that home.”

For their final few years of captivity, Castro treated his captives more liberally. They were no longer chained up, but simply locked up. Knight and DeJesus were allowed time to see the baby. Does she think that in some way Castro might have loved them? “In his sick way, yeah. In his own demented mind, he loved all of us because he thought we were all family. That goes back to his fake world where he wanted a family and he didn’t have it. He always complained about how his family had left him, abandoned him.”

When Castro was discovered hanging by his bedsheet last September, it was assumed he had taken his own life. But the Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction then released a report saying he might have died accidentally, from auto-erotic asphyxiation. Coroner Dr Jan Gorniak rejected this, standing by her original ruling of suicide. Knight agrees with the coroner: “All I believe is he took the coward’s way out.”

Does she wish he was still in prison? “Well, I kind of wish he didn’t kill himself, but to each his own mind. He didn’t want to be alive. He couldn’t take what he did. And I understand that. If I was him, I’d have taken my own life, too.”

We are playing pool on Knight’s micro table, and she is laughing at my inability to manoeuvre the tiny cue. She loves sport: last night she went to basketball, today she is off to a baseball match. Peggy Jones says Knight’s appetite for life never ceases to astonish her. She goes to the theatre, she goes to concerts, she is a night owl. “I can’t keep up with her. When we travel and she wants to go clubbing, I just can’t do it.”

They go clubbing together? Suddenly, these two very different women are in hysterics.

“She taught me how to dance,” Jones says.

Knight is laughing so much she can barely get the words out. “I was teaching her how to dance and she looked as if she was having a seizure.”

I ask Jones what she hopes for most for Knight.

Inside the house, she wrote a list for an imaginary camping trip: underwear, sleeveless T-shirt, long sleeves for when it’s cold, shorts, long johns, socks, compass, hiking boots, peanuts, chocolate-chip cookies, pegs.’ Photograph: Christopher Lane for the Guardian“To heal. I’d like you to get your stomach sorted. I’d like you to be healthy, physically and mentally. I hope you can fulfil your dream. I don’t know whether it will be running a restaurant or singing, but I know you’ve got the confidence and discipline to do it. But it will be a lot of hard work.” Jones, tough, polished and immaculate, starts to wobble. She dabs her eyes.

Inside the house, she wrote a list for an imaginary camping trip: underwear, sleeveless T-shirt, long sleeves for when it’s cold, shorts, long johns, socks, compass, hiking boots, peanuts, chocolate-chip cookies, pegs.’ Photograph: Christopher Lane for the Guardian“To heal. I’d like you to get your stomach sorted. I’d like you to be healthy, physically and mentally. I hope you can fulfil your dream. I don’t know whether it will be running a restaurant or singing, but I know you’ve got the confidence and discipline to do it. But it will be a lot of hard work.” Jones, tough, polished and immaculate, starts to wobble. She dabs her eyes.

I ask Knight what she can remember of the day she escaped. Berry had managed to attract the attention of neighbours, who called 911. Knight says she didn’t believe it was the police battering down the door – she thought it was a break-in. “I was like, nah, anybody can just say, ‘Police.’ I didn’t think she actually was, till I heard the walkie-talkie. Once I’d seen a police badge, and police lady, I just ran out of the door and jumped into her arms and grabbed hold of her and wouldn’t let her go. I didn’t think it was real. I turned round and saw Gina and my mind was spinning like heck, and I said, ‘Hey, do you know what we’re doing? We’re going home, we’re going home!’ ”

But while DeJesus and Berry had homes to go to, Knight didn’t. Sure enough, her family turned up, but she wasn’t interested; she moved into the sheltered accommodation. “My mother says she always loved me, when she never loved me at all. All the things she said on the news: we owned a farm, I had a horse. I never lived on a farm, I never had a horse. Just be real. That’s all I want from her, to be real.” Barbara Knight denies she was a bad mother and last autumn told an US TV show: “Her point of view has been altered by that monster and what he did to her. What I’ve heard that she said about me breaks my heart.”

Knight has not seen Berry and DeJesus, either, but she is convinced that will happen in time. (The three girls were originally asked to write a book together, but Knight felt she had a different story to tell and chose to write her own; DeJesus and Berry’s account will be published next year.) “Right now we’re all going through our own separate problems. We need to take time for ourselves.” As for Joey, he is now 14, and she has seen pictures of him and written letters. But she knows she can’t rush anything, and that he will probably regard his adoptive parents as his true parents. “He is a beautiful, handsome man, and I love him to death. I’m glad he has all that he has got now; I’m sad I’m not there. I hope one day we’ll get together, have a cup of coffee, whatever.” She says that even more than DeJesus, it was the thought of Joey that kept her going.

You know you asked me how I got through those 11 years, she asks. She takes out a pile of paper – drawings, poems and writing she did in the house. Much of it is dedicated to Joey. She reads a letter to him, slowly, because of her eyes. “It says, ‘Happy halloween, son. I love you and wish I was there at home. All I got at the moment is a memory of you.” She shows me a card she made of a dog wearing a mortar board. “This was to celebrate his graduation from nursery.” Amid the piles of writing, there are lists – of plans, of dreams, of needs, all made in the house. One list says, “Shampoo, towels, bath cloths, toothpaste”. “Things we didn’t have but we wanted,” she explains. “We didn’t usually have toothpaste. He’d give us a tiny bit and expect it to last six months. When he gave us peroxide or alcohol for cuts, I’d use it to brush my teeth.” Another list she wrote names everything she would need for a camping trip. She reads it out, matter of factly. “It says, ‘Underwear, sleeveless T-shirt, long sleeves for when it’s cold, shorts for during the day, long johns, socks, sleepwear, shoes, compass, hiking boots, bathing suit, hats, gloves, raincoat, rain-pants, peanuts, raisins, chocolate-chip cookies, dried fruit, cereal, water, marshmallows, pegs.’ ”

Recently Knight changed her name by deed poll to Lily Rose Lee (Lee is Joey’s middle name). “I just love the name, and the names that I already have I don’t like too much. It’s about making a brand new start. I didn’t want people to know me as that girl. I want people to know me as thisgirl.”

She has also treated herself to a number of piercings and tattoos, which she guides me through. First her left arm. “This one is my protection dragon, turns everything that was dark into light.” Then a Care Bear on her upper arm. “This one is for my son, he’s my little huggy bear.” There is a dramatic tattoo on her leg featuring two guns. It reads, “Know me as a victor not a victim.” She lifts her right arm to show a tattoo of a baby with black hair. “This one represents the baby that passed away in the house. I call her my little angel.” I’m unnerved as I realise I’m looking at both the face of Castro and her imagined baby in one tattoo. Does it not remind her of Castro? “No,” she says decisively.

Finally, she uncovers an expansive tattoo on her back and shoulders: a pair of wings inscribed with “Freedom to fly”.

The afternoon sun is dazzling. I ask if she always keeps the blinds open. “Yes, I do,” Knight says. “It’s to see the beautiful sky that I never saw for years.” She is squinting into the sun. Do her eyes hurt? “I still have bits of problems. If the sun was beaming bright, I’d have to stay back from the window.” Are her eyes improving? “Right now they’re not, but hopefully they will. I still got hope.”